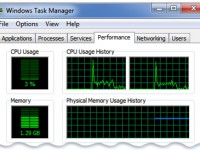

Most operating systems have some method of displaying CPU utilization. In Windows, this is Task Manager.

Most operating systems have some method of displaying CPU utilization. In Windows, this is Task Manager.

CPU usage is generally represented as a simple percentage of CPU time spent on non-idle tasks. But this is a bit of a simplification. In any modern operating system, the CPU is actually spending time in two very distinct modes:

- Kernel Mode

In Kernel mode, the executing code has complete and unrestricted access to the underlying hardware. It can execute any CPU instruction and reference any memory address. Kernel mode is generally reserved for the lowest-level, most trusted functions of the operating system. Crashes in kernel mode are catastrophic; they will halt the entire PC.

- User Mode

In User mode, the executing code has no ability to directly access hardware or reference memory. Code running in user mode must delegate to system APIs to access hardware or memory. Due to the protection afforded by this sort of isolation, crashes in user mode are always recoverable. Most of the code running on your computer will execute in user mode.

It’s possible to enable display of Kernel time in Task Manager, as I have in the above screenshot. The green line is total CPU time; the red line is Kernel time. The gap between the two is User time.

These two modes aren’t mere labels; they’re enforced by the CPU hardware. If code executing in User mode attempts to do something outside its purview– like, say, accessing a privileged CPU instruction or modifying memory that it has no access to — a trappable exception is thrown. Instead of your entire system crashing, only that particular application crashes. That’s the value of User mode.

x86 CPU hardware actually provides four protection rings: 0, 1, 2, and 3. Only rings 0 (Kernel) and 3 (User) are typically used.

If we’re only using two isolation rings, it’s a bit unclear where device drivers should go– the code that allows us to use our video cards, keyboards, mice, printers, and so forth. Do these drivers run in Kernel mode, for maximum performance, or do they run in User mode, for maximum stability? In Windows, at least, the answer is it depends. Device drivers can run in either user or kernel mode. Most drivers are shunted to the User side of the fence these days, with the notable exception of video card drivers, which need bare-knuckle Kernel mode performance. But even that is changing; in Windows Vista, video drivers are segmented into User and Kernel sections. Perhaps that’s why gamers complain that Vista performs about 10 percent slower in games.

The exact border between these modes is still somewhat unclear. What code should run in User mode? What code should run in Kernel mode? Or maybe we’ll just redefine the floor as the basement– the rise of virtualization drove the creation of a new ring below all the others, Ring -1, which we now know as x86 hardware virtualization.

User mode is clearly a net public good, but it comes at a cost. Transitioning between User and Kernel mode is expensive. Really expensive. It’s why software that throws exceptions is slow, for example. Exceptions imply kernel mode transitions. Granted, we have so much performance now that we rarely have to care about transition performance, but when you need ultimate performance, you definitely start caring about this stuff.

Probably the most public example of redrawing the user / kernel line is in webservers. Microsoft’s IIS 6 moved a sizable chunk of its core functionality into Kernel mode, most notably after a particular open-source webserver leveraged Kernel mode to create a huge industry benchmark victory. It was kind of a pointless war, if you ask me, since the kernel optimizations (in both camps) only apply to static HTML content. But such is the way of all wars, benchmark or otherwise.

The CPU’s strict segregation of code between User and Kernel mode is completely transparent to most of us, but it is quite literally the difference between a computer that crashes all the time and a computer that crashes catastrophically all the time.